“Sixty years of crowd management has

made Disney operations the undisputed champion of event control and

coordination….If you’re serious about solving [your traffic] problems, you go

to the Disney Academy at Disney World.”

--

Phil McKinney, innovation expert, Beyond the Obvious, 2012

Over the past century, the Disney Corporation has exerted an

outsized effect on popular culture and the popular arts. Disney 100, this year’s centennial of the

company’s 1923 founding, is a timely point for taking stock of the “Disney

Effect” across major cultural domains—especially in the domain of “themeatics. “

Since 1955 at Disneyland, the Ur-theme Park, the Disney model

has guided design basic to the experience economy, acting as centers for

creativity and innovation in the arts and technology, both popular and elite. Themeing has been transforming public space

in both design and use as enlargements of the sphere of entertainment far

“beyond the berm,” most unforeseen and not at all calculated on the part of

D-Co. My career knowledge in themeatics

(as I’m calling the aggregated skill set that created theme parks) can be put

to work to take a measure of the far-reaching effects of this legacy.

Themeatics is the unified field theory for the arts, as an artform that

underpins design across fields from architecture to city planning to drama and audience

experience to graphic design. Every aspect of the designed environment has been

informed by the Disney Metropolitan Deco template. Around 150 artistic

subfields, as a conservative estimate (by the late Marty Sklar as President of

Walt Disney Imagineering) can be enumerated; and any artform ever devised, from

ancient to state-of-the-art, can be seen within the fabric of the park design.

Walt Disney himself is considered a master innovator in the

arts (all genres) and technology (high- as well as low-tech), with theme parks

as the incubator enjoying a test audience of millions per month. Far from Disney’s initial reputation as an

animator (his true role was as a story editor and creator of the synchronized

sound cartoon) and entertainer of the nation’s children with cartoons and audio

animatronic rides, he headed a studio led by Imagineering (“imagination plus

engineering”) that soon became a center for interdisciplinary creativity and

innovation. The outcomes transformed

public space and the way it could be used, enlarging the entire scope and influence

of simple entertainment.

Central to this role was the development of hyperreality

as the ultimate adaptable format for designing as well as experiencing art as a

total-immersion, mixed-media, seamless experience. Art and technology became permanently conjoined,

using augmented reality (AR) from digital programs and applications, the basis

of 5-D multi-media. The outcome was

environmental artworks, the most iconic being the theme park, aimed at brains

and bodies of all ages.

Hyperreality melds the real with

fantasy and the subconscious so that these become indistinguishable in a new

amalgam—as in the transformation of history on Main Street, USA. As Christopher Finch put it in The Art of

Walt Disney as early as the 1970s, “Disneyland and Walt Disney World are

shows—a kind of total theater which exceeds the wildest dreams of avant-garde

dramatists.” Hyperreality is a concept

in post-structuralism that refers to the process of the evolution of notions of

reality, leading to a cultural state of confusion between signs and symbols

invented to stand in for reality, and direct perceptions of consensus reality.

Hyperreality is seen as a condition in which, because of the compression of

perceptions of reality in culture and media, what is generally regarded as real

and what is understood as fiction are seamlessly blended in experiences so that

there is no longer any clear distinction between where one ends and the other

begins. Hyperreality – established within the popular arts as well as the elite

levels--works to integrate emotion, memory, rationality (as art history), and

cultural values for both brain and body.

Culturally, at the theme parks,

hyperreality acts as the enveloping artform to showcase themes important to cultural

values for Americans; they express those values we most favor about ourselves

and our national heritage: collective imagination (Fantasyland), our shared

vision of the future (Tomorrowland), other people, places, and adventures

important to us (Adventureland), and American history in Frontierland and Main

Street, USA.

At the theme park, the Disney Effect

is an influence in entertainment and edutainment on all fronts. Here the distinction between entertainment

(as engagement) and amusement (as diversion) emerges. Disney productions and

their methods are major instigators of the entire Experience Economy identified

by Pine and Gilmore in 1999.

Further, the Creative Economy,

reflected in the Experience Economy, considers public space a closely designed

and deliberate event-integrated vision--as seen in animation art. The Disney

Imagineering team is cross-functional and interdisciplinary, a template copied

across creative industries, for example in the use of storyboards to diagram

character and action, an aspect of “blue-sky” open-ended idea generation.

The Disney legacy can be traced through the decades across a

range of creative industries, tools, and technologies that inform the designed

environment. Theme parks in particular

have become urban labs where concepts can be experienced by millions of

visitors to test viability.

Perhaps no other artform innovation

approaches the reach, persistence, and inspiration as clearly as the legacy of

this prototype. Themeatics is a

hyperreal mix of techniques borrowed from animation and filmmaking rather than

architecture and urban planning: the familiar storyline, identifiable

archetypal style, “not the design of space but the organization of procession”

(architect Philip Johnson); stagecraft, iconography, special effects,

audio-animatronics (3D animation), and color coordination, all led by the

concept of “show” and “enhanced reality” (the late senior Imagineer John Hench’s

term). Themeing is a tightly focused reality made to evoke specific times and

places with strong cultural resonance.

These distillations – from musical cueing and food to landscaping,

lighting, scaling, signage, sound, surface, texture, and smell--play off

perception and collective memory to create “instant moods.” These are achieved

by motifs, layered detail (fractals), and multi-sensory environmental designs,

favoring images over text to tell stories and give emotional direction.

Inherent in themeing’s sense of place as a theater stage is the legacy of

revival or nostalgia in latter twentieth-century design, and the multi-media

assemblage of artforms and styles from many eras, traversing the evolutionary

range from craft to high-tech.

Such a far-reaching and durable “Disney effect” was unintended and

unanticipated; co-evolving with the unforeseen ascendence of virtual reality as

a new default resulting in hyperreal environments. The theme park model would recreate the real

world both within and outside it, multiplying other worlds as themeatic offshoots.

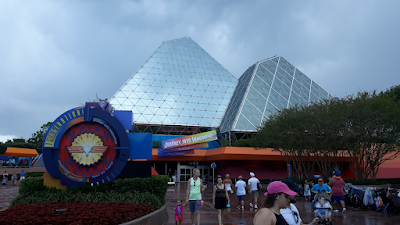

Journey

into Imagination photo by J.G. O’Boyle