“We suggest that the question for scientists should instead be: if we adopt the definition from computer science, then what kind of a computer are brains? For those using the definition from outside of computer science, they can be assured that their brains work in a very different way than their laptops and their smartphones—an important point to clarify as we seek to better understand how brains work.” – “The Brain-Computer Metaphor Debate Is Useless,” Richards and Lillicrap, Frontier, Feb.8, 2022

Stage 1 - Image from Aeon

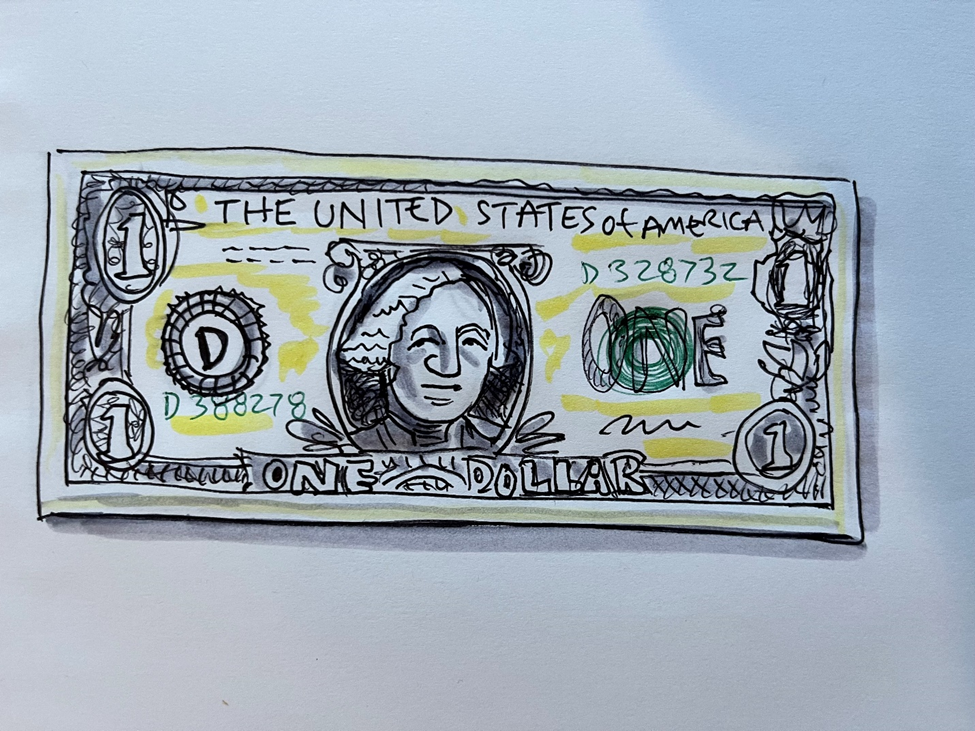

Without looking in your wallet, try this: Draw the portrait side (the “obverse”) of a

$1.00 bill. How did you do? Does it look like a child drew it? (Stage 1) How many times have you looked at this exact

same object? Certainly thousands and

thousands. Then why isn’t it stored

somewhere in the brain, ready to leap onto the page? (Robert Epstein took on this question and its

implications in 2016 in an article called “Your Brain is Not a Computer” in Aeon).

Although the metaphor is alive and active, the information

processing theory of the brain (active since the 1940s) is not only misleading,

because our brains are not uploaded, downloaded, or a cluster of coded

programs, but prevents seeing our unique capabilities, which aren’t even

parallel to those of computers. Each

human brain is uniquely shaped by its own experiences (not “inputs’) and in

fact gets “rewritten” in different ways.

We each learn differently, creating new knowledge from our unique

abilities to live and learn from those experiences. We change and create constantly because we

aren’t coded to one system for handling information—though we are biased

socially in the direction of the culture we inhabit. This is the reason our brains can’t be

downloaded to a computer. Brains don’t

store words, images, or symbols—we don’t retrieve or download memories. It could be called the “One percent reality

problem” – we live in our heads, not in anything like an objective reality

sphere.

Memory is one reason we operate day to day on incomplete

information. Our perception is sketchy,

our memories are full of holes, and our general knowledge studded with gaps. In

trying to recall and draw a dollar bill you will get a crude drawing with main

features only.

Juries have this problem with evidence, as well as employers

looking for recruits, marketing looking for purchasing motives, by drawing

conclusions from limited cues. This is

what culture does: it helps us think and decide on the basis of very limited

information. Name bias—attempting to

size up people by last / first name, is one example.

In his book Things that Make Us Smart (1993) Don

Norman says, “We are excellent perceptual creatures who see a pattern and

immediately understand it. Another

common phrase used in psychology to describe this state is ‘going beyond the information

given.’ A simple fragment of information

and we immediately recognize the whole…Sometimes we can identify a friend or

relative from a cough or footstep.”

Sampling yields errors for infrequent events and/or people. The brain processes images against a

stereotype list – a shortcut to pick out a person, object, place, or symbol. It looks over this patterns list to match up

the perceived pattern with something already familiar. In this way, acts of perception are always

acts of plumbing the past to resolve unknowns in the present. And as a whole class of studies has shown, this

list is scattered, imprecise, and set up to be misleading.

However, through the magic of adapting ideas to their current use, it works for us. We know to look at a real dollar bill to resolve our mental picture of it to clarify relationships and correct errors. (Stage II)

Stage II - Artist’s rendition of the $1 bill

Intelligence

In making hundreds of thousands of connections, human intelligence

lies not in the number of neurons in the brain but in the connective system

between brain cells. This connectivity

of ideas and images is the basis of adaptive intelligence and creativity. But from a computing standpoint, this system

is far from stable, and is prone to the fluidity of memory and subject to so

many “errors” that it could never be considered an accurate system of fixed

facts and figures.

Memory

Cognition is anything but a precise system. We live in our heads, not only in our imaginations,

but in the imaginative reconstructions of reality that occurs every time we

remember and reconstruct the reality we live in. We process the raw materials of memory and

what is around us (perception) to create a meta-reality, our version of

reality, which corresponds roughly to the reality as it exists and as it exists

for other people. This is why culture

exists as the web of ideas (illusions) that bonds us to the brains of

others. Culture is the shared idea of

reality that we can reference and rely on—and reshape to any number of

uses. This is the way we develop our

capacity to interact with the world effectively. We don’t retrieve memories – we refashion

them to our current needs.

Hard v. Soft technology: Logic v. Language

Technological systems can be classified into two

categories: hard and soft. Hard tech refers to those systems that put

technology first, with inflexible rigid requirements for the human. Soft tech refers to compliant, yielding

systems that “informate,” providing a richer set of information and options

than would otherwise be available, and most important of all, acknowledge the

initiative and flexibility of the person.

Norman continues by noting that the language of logic does

not follow the logic of language. Logic

is a machine-controlled system in which every term has a precise

interpretation, every operation is well-defined (rigor, consistency, no

contradictions, no ambiguities). Logic

is very intolerant of error. A single error in statement or operation can

render the results uninterpretable. On

the other hand, language is always open to interpretation and fine-tuning,

which is the essence of dialogue and its logic of directed correction and

clarification.

Language is indeed quite different. Language is a human-centered system that has

taken tens of thousands of years to evolve to its current form, which exhibits

in the multitude of specific languages across the globe. Language has to serve human needs, which

means it must allow for ambiguity and imprecision when they are beneficial, be

robust in the face of noise and difficulties, and somehow bridge the tradeoff

bet ease of use. and precision and accuracy (longer and more specific). At its base, any language has to be learnable

by young children without formal instruction, be malleable, continually able to

change and adapt itself to new situations, as well as very tolerant of error.

Like language, then, pattern-making usually works well

enough so that we think of it as reliable. As larger-than-life patterns,

stereotypes have earned the bad reputation of occasionally being wrong. But against that liability is the evidence

that they are usually reliable. If this

were not the case, they wouldn’t proliferate or have any reputation at all to

worry about

“Archetype” is a better way of thinking about our thinking –

ideal prototypes (from the Greek “original pattern”) that represent whole

categories. Types are the basic currency

in which our minds deal, and the cast of myths and storytelling. Especially central in thinking about people,

as in Jung’s 12 universals, they are balanced by the persona or self at the

center—Latin for “mask.” Understanding

the world effectively has a strong link to drama and themeing—very far from the

stage of computing.