“Without changing our

patterns of thought, we will not be able to solve the problems that we created

with our current patterns of thought.”

--Albert Einstein

Bias Part II

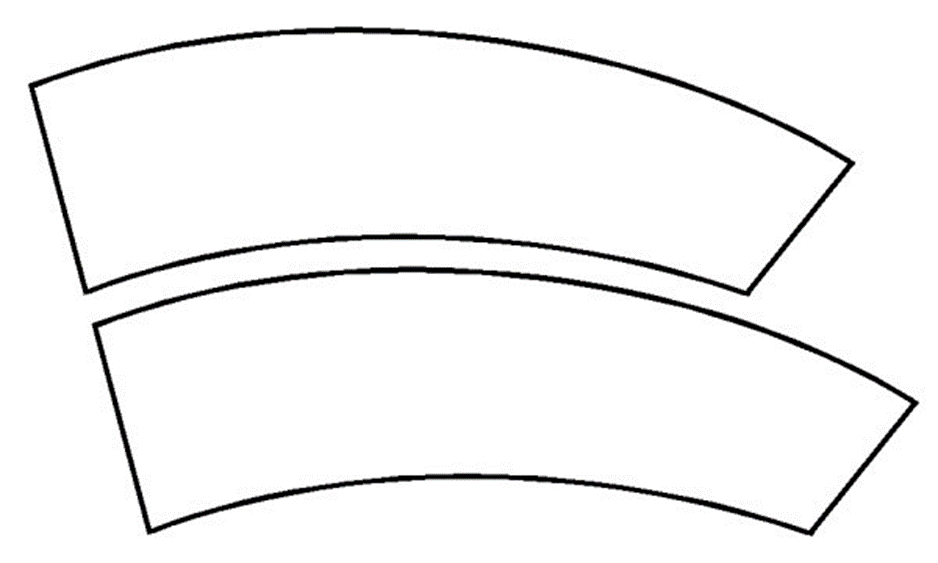

THE JASTROW ILLUSION

Compare these two stacked curves. Which is longer? This is a classic optical illusion, from the nineteenth century. In fact, the two are actually identical. The illusion vanishes with a change in perspective to upright/vertical. The human brain is automatically comparing everything it sees.

Ranking is a human proclivity, and it

is all around us. SEO (search engine

optimization) ratings, US News Best Colleges, The Olympics, pro sports and

amateur sports, Amazon product reviews, happiness rankings of countries

worldwide, employee job applications, political candidates’ approval ratings,

reputation polls. In fact, it is impossible for anyone to examine two objects

within the same category without ranking them in some way on some feature. These can include reputation, performance, brand,

cost, design, range of uses, aesthetics, color, size, speed, efficiency, and

dozens of other basic aspects. Think

about the time and energy we all expend in comparing ourselves to others. We compare along these lines and beyond –

without having any way of confirming these ratings except a general anxiety

about the need to do so. Our social media scores are a simple example.

Dominance

Top Ten lists are everywhere and cover

everything imaginable, including longest reigning monarchs, youngest state

leaders, no-hitter record pitchers, highest jumpers, most innovative countries,

winning tips for college-level essays, video game characters, famous

astronauts, hang-gliding champions, chess minds, Noble Peace Prize winners, teams

with the largest stadiums, quickest female Paralympians, and, of course, Best

Top Ten lists. The recent obituary of

singer Harry Belafonte ranks him as the first Black Emmy and Tony Award winner

as well as the first of any race to sell one million albums (“Calypso,” in

1956). (The Week, May 12 2023)

Our hourly ruminations consist of

searching for clues to our standing compared to others. Talent, wealth, perception, power, influence,

trustworthiness, and romantic interest are all rankings we seek to compete and excel

in. These are dominance hierarchies in

every society, and they serve a purpose.

As systems expert Peter Erdi puts it in his book Ranking, “Dominance

hierarchies are very efficient structures at very different levels of

evolution. They have a major role in

reducing conflict and maintaining social stability…to regulate access to these

resources [food and mates].”

Dominance ranking is a great mechanism

to maintain the status quo, so that people (and animals in general) have a good

idea of where they stand, and where they would like to stand in the future. Dominance goes beyond power, leadership, and

authority to include influence, expertise, competence (toward virtuosity), and

trustworthiness (a brand of social equity).

Think of writers, athletes, musicians, artists, and inventors and their role

as models of prestige.

Emergent properties

Ranking and valuing have their

value. But what are the emergent

properties, the unanticipated outcomes, of ranking competitions? There are costs. They begin with the constant need to measure

and judge, ending often enough in an ongoing critical evaluation of self as never good

enough. Constant comparison is the

essential activity of social media worldwide.

The Zoom screen affords the

opportunity-as-compulsion to see oneself alongside others. The self-criticism and appraisal of our

appearance up against others in the screen meeting is one reason that remote

meetings are as stressful as they are, regardless of the business at hand. And while we are comparing ourselves to others

on dozens of scales, they are doing the same.

No one entirely knows what their score is, but act as if they do. Billionaire investor Charlie Munger (Warren Buffet’s business partner)

declared “The world is not driven by greed.

It's driven by envy.”

The obsession with determining

the best of everything is a form of “virtue bias,” the directive we all share

to seek out a way that lets us agree on rankings for everything from colleges

to cars to cappuccinos. So we curate

“best of” lists for everything. Whatever

their standards, and whether those standards are based on tangible and provable

truths, these lists take on a life of their own, reinforcing themselves in a

self-fulfilling prophecy as the most-cited attract to become the most-desired and

best-selling.

The cost of

competition is then passed along to those underneath the top ranks—the second

place to mediocre to loser class. Which,

because so few of us are winners (on one scale, let alone several), means that we

all tarred by the bias against “second-best,” or as a colleague once phrased it,

“First Loser.” That’s not a great-sounding

placement, considering all the effort put out to make something of our lives

and our reputations. Just a reminder

that talent is not equally distributed.

Neither is the work ethic necessary to maximize that talent. This is why equality is such a tricky concept

to pin down and engineer. The social contest is not a

level playing field, and some of that levelling is under our own control, while

the start-points—family, location, culture, ethnicity, wealth, class—are more steeply

slanted as well as harder to equalize later in life.

These contests, in operation in

all domains of life, are one way to find information useful in making choices

and investments of our time, money, and attention. To this end, we seek out the best possible in

schools--including preschools--for our children, politicians who will represent

our interests, cars we can rely on to confer status as well as deliver performance, books that will reward the time investment in reading them. We seek out friends who will enhance our

efforts by reinforcing our values, making them worth the precious time invested

in socializing. We hope for college roommates whose

good character and work habits will encourage our own school success (as

important, some studies show, as the quality of the school attended). President-to-be Franklin Pierce had such a

roommate at Bowdoin College, one who fired up his ambition and work habits. Homes

in the most advantaged parts of town we can afford in order to enjoy quality

neighbors. Colleagues to match our

interests and our goals and lifestyles. Marriage partner, ditto. Such preferences are quality-control devices,

deployed as systematic bias protection against making poor judgments by our

social group.

Ratings are supposed to help us distinguish

between good and less effective use of our resources: time, wealth, energy,

reputation. Life is largely an

efficiency game, one we seek to win at as often as possible, by aiming to win each

time.

Outcomes and correctives

When recorded music became

available by record and radio, everything else started to sound amateurish, or homegrown,

or less-than-professional (John Phillip Souza, consummate composer in many

genres, predicted this effect of technology).

The music on the ground, as it migrated onstage, created its own

recording traditions that nationalized the genre (like folk, country, blues,

and jazz), leading to its own “best-of” listings. Belafonte’s signature “Banana Boat Song,”

“Day-O,” is a Jamaican work song out of the colonial island fields but massaged

by studio technologies, headed the charts in 1956. Songwriters led by “the father of American

music,” Stephen Foster, could be rewarded for their talents thanks to copyright

and printing advances.

In the workplace, to compensate

for the seller’s market in computer talent, companies are starting to adopt

“skills-based hiring” to get around degree-based ranking of job applicants. Applied

computer skill doesn’t require the traditional four-year degree or professional

title, and can be conducted on-line and on the associate level. Distinction between certification and

performance is the focus, opting for evidence-based performance over degree awards. By the same mentality, merit-based admissions

values achievement over race-based pro-bias in college admissions. Affirmative action continues to be an ongoing

debate that pits achievement against adjustment in the cause of balance and

fairness. To erase any competition for

recognition, Santa Monica High School in California has done away with its Honors

program in English as an enabler of inequality. Not without concern over loss of opportunity for bright contestants who are now losers of this resume benefit.

Even bat-flipping in

professional baseball, the practice of tossing

the bat in the air to celebrate a home run, is a

point of debate. The practice was labelled as disrespectful of the

opposing team and the game itself. More recently flipping the bat

is being viewed increasingly as simply a

celebratory exhilaration and not an insult – realigning expectations and

allowing for a more expressive game. Even the slightest ritual carries

with it a bias-based value.

All bias depends on expectations

and context as a culturally constructed virtue or vice. From the birth of human society, nonetheless, physical height is still positively correlated with leadership potential and dominance

in pecking orders. Erdi notes that “the

desire to achieve a higher social rank appears to be a universal, a driving

force for all human beings.”